The Early Days

The Next Generation

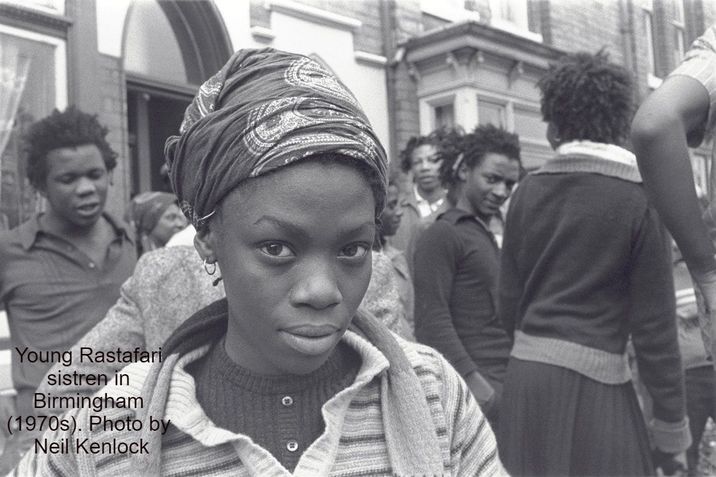

The Rastafari Movement entered a new phase when it was picked up by the post Windrush generation – those who were either born or schooled in Britain. Marginalised by a Eurocentric education system, alienated from mainstream British society, ill fitted for the labour market, the next generation found inspiration in the Rastafari philosophy of Black pride and resistance that was transmitted through their Caribbean heritage.

Listen to acclaimed film direct Menelyk Shabbaz talk about the Rastafari influence on these youth:

Listen to acclaimed film direct Menelyk Shabbaz talk about the Rastafari influence on these youth:

Rastafari radicalized many Black youth. The idea that Britain was Babylon - a sinful place - populated by "Baldheads" - evil-doers - made sense to many young people whose formative years were shaped in part by the institutional racism they met in the school, on the street, in the courts, and in the workplace.

|

Here is a poem by a young Benjamin Zephaniah, listed in the top 50 greatest post-war British writers, but whose formative years were influenced by Rastafari and the "sound system" culture in Birmingham:

Baldheads Believe Baldheads believe hear say Dem hear say every day, Baldhead people very feeble Going down dead way, Dreadlocks don't check hear say No chance dis time round, Dreadlocks deal wid rockers And heavy Reggae sound. Is no fornication Living upful good, Dancing to the moving beat in every neighbourhood, Baldhead worship devil, Dread one smoking pipe, Getting to the level just like fruit, well ripe. |

The radicalization of the youth, through their embrace of Rastafari, set some of them on a collision course with their more conservative parents and family. Take, for example, this testimony by one "Sister Bev":

And consider this evidence collected for the Home Affairs Committee, Race Relations and Immigration Sub-Committee between 1980-1981:

Is there much Rastafarianism in Leicester?

(Miss Paul) You make it sound like a disease. Rastafarianism is a religion and it also has a cultural base. There are many young people who are Rastafarians. Some have chosen it perhaps on the basis my organisation’s Chairman has said, dropping out of society, because of experiences of an extremely negative kind within the host community. Some have chosen it on an intellectual and religious basis. But there is a considerable number of young people, male and female, who are Rastafarians; it is a growing religion.

Are you a Rastafarian yourself?

(Miss Paul) I do not subscribe to any particular religious group as such.

Do you think that it does actually provide any of the self identity that you were talking about?

(Miss Paul) Yes, most certainly.

Is it not true that a great many of the West Indian community doubt whether it does and find it destructive?

(Miss Paul) One has to look at the underlying reasons. Many of our parents, which would be the main category that would find the Rastafarian development within our community disturbing, see it as perhaps a failure in themselves. Many, like my own parents and other parents, have brought up their children, particularly those born here, to feel that the British way of life was the only way of life; not only that but you were going to get jobs and justice and opportunity and everything that they had never achieved. In saying that, they made us as English as possible. Many taught their children to deny their own food for one thing; many children do not like to eat West Indian food at a very early stage; and they go on into their teens when they reaffirm who they are. When you have got that at the very base you have a situation where the Rastafarian movement comes as a threat. There is a change in dietary habits, a change in dress, and in hair style. Many of our parents would have liked us to look as white as possible; so their children, particularly girls, are submitted to constant savagery on their hair, of hair straightening to make them look as pretty and as white as possible. The Rastafarian has the notion

of letting his locks grow naturally. This is seen as something perhaps not fitting in line with the white model that our parents prefer us to pursue.

Is there much Rastafarianism in Leicester?

(Miss Paul) You make it sound like a disease. Rastafarianism is a religion and it also has a cultural base. There are many young people who are Rastafarians. Some have chosen it perhaps on the basis my organisation’s Chairman has said, dropping out of society, because of experiences of an extremely negative kind within the host community. Some have chosen it on an intellectual and religious basis. But there is a considerable number of young people, male and female, who are Rastafarians; it is a growing religion.

Are you a Rastafarian yourself?

(Miss Paul) I do not subscribe to any particular religious group as such.

Do you think that it does actually provide any of the self identity that you were talking about?

(Miss Paul) Yes, most certainly.

Is it not true that a great many of the West Indian community doubt whether it does and find it destructive?

(Miss Paul) One has to look at the underlying reasons. Many of our parents, which would be the main category that would find the Rastafarian development within our community disturbing, see it as perhaps a failure in themselves. Many, like my own parents and other parents, have brought up their children, particularly those born here, to feel that the British way of life was the only way of life; not only that but you were going to get jobs and justice and opportunity and everything that they had never achieved. In saying that, they made us as English as possible. Many taught their children to deny their own food for one thing; many children do not like to eat West Indian food at a very early stage; and they go on into their teens when they reaffirm who they are. When you have got that at the very base you have a situation where the Rastafarian movement comes as a threat. There is a change in dietary habits, a change in dress, and in hair style. Many of our parents would have liked us to look as white as possible; so their children, particularly girls, are submitted to constant savagery on their hair, of hair straightening to make them look as pretty and as white as possible. The Rastafarian has the notion

of letting his locks grow naturally. This is seen as something perhaps not fitting in line with the white model that our parents prefer us to pursue.